Multiple Tumors in Pituitary Gland Can Cause Cushing’s Disease, Case Report Contends

Written by |

When multiple tumors in the pituitary gland lead to overproduction of hormones besides ACTH, patients may have features of Cushing’s disease and a wide array of additional symptoms, a case report suggests.

The study, “Double pituitary adenomas with synchronous somatotroph and corticotroph clinical presentation of acromegaly and Cushing’s disease,” appeared in the journal World Neurosurgery.

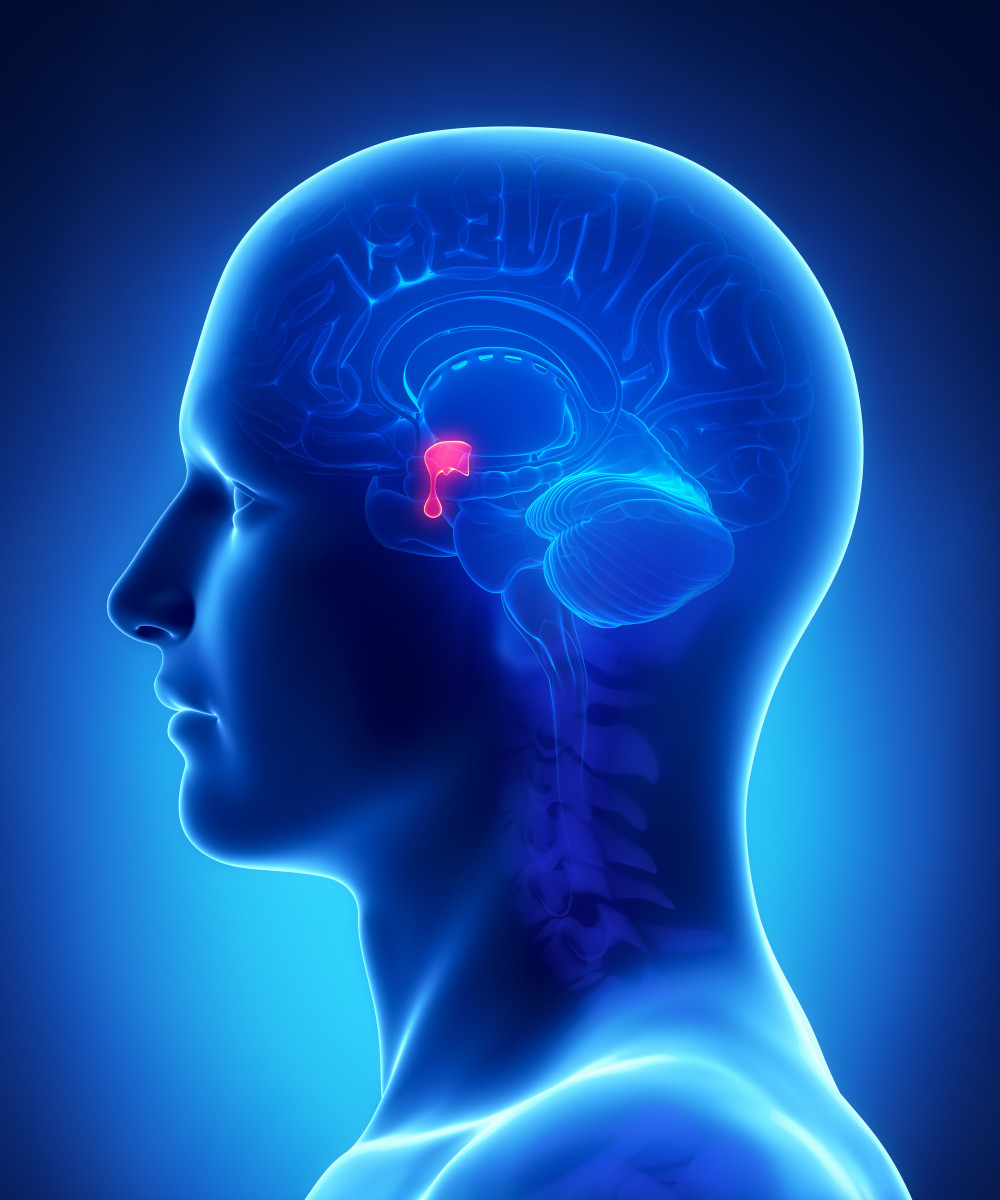

Cushing’s disease is usually caused by a tumor in the pituitary gland that secretes too much adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), leading to excessive production of cortisol. In some rare cases, there might be multiple tumors in the pituitary gland, or a tumor can secrete other hormones, such as prolactin or growth hormone, besides ACTH.

Researchers in Puerto Rico reported the case of a 51-year-old woman who developed Cushing’s disease and acromegaly — abnormal growth of the hands and feet that occurs when adults produce too much growth hormone — caused by two tumors in the pituitary gland that secreted ACTH and growth hormone.

The woman arrived at the hospital complaining of shortness of breath, pain in the joints and muscles, weakness, decreased libido, and headaches that had been going on for two years. She also reported necessary increases in her shoe and ring size.

The patient had high blood pressure since adolescence and recently had been diagnosed with type-2 diabetes.

Physical examination showed that the woman was obese; she had gained 15 kg (about 33 pounds) in the past year. Blood pressure was slightly high in spite of the medication.

Lab exams showed elevated somatomedins — proteins produced by the liver in response to growth hormone — and cortisol in the saliva and urine. A high-dose dexamethasone suppression test reduced the cortisol levels, which confirmed the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s disease.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested the presence of multiple tumors in the pituitary gland. The doctors performed surgery and removed two tumors; one of them produced ACTH, and the other produced growth hormone.

Cortisol levels after the surgery were on the higher side of the normal range, which made doctors suspect they did not remove the whole ACTH-producing tumor. Nonetheless, the patient started replacement therapy with hydrocortisone.

Shortly after the surgery, the woman developed diabetes insipidus, a condition that causes a liquid imbalance, leading to excessive loss of water in the urine and constant thirst.

Three months after the surgery, her cortisol levels had increased and were again above the normal range. A second MRI confirmed there was some left-over tumor in the woman’s pituitary gland.

One year after the surgery, the woman still needed to take medicine to control her glucose levels, but her high blood pressure had improved significantly, so doctors tapered the dose of her medication. Cortisol levels in the urine and saliva were normal.

“Our patient will need long-term surveillance due to residual tumor at the cavernous sinus although at one year after the surgery there is no evidence of [excessive production of hormones by the pituitary gland],” the researchers said.

The case is the third report of a patient with multiple pituitary tumors producing ACTH and growth hormone, in which both hormones caused symptoms.

The investigators noticed that cases of multiple pituitary tumors increase the risk of failure after surgery because some tumors might not be removed completely. They concluded that in cases of multiple tumors in the pituitary gland “extensive surgical exploration … must be performed to avoid surgical failures from residual tumor.”

“Follow-up is recommended for all patients after successful surgical removal of hormonally active pituitary tumors,” they said.