Blood Clot Risk in Cushing’s Disease Patients May Extend Well Beyond Pituitary Surgery, Case Study Finds

Written by |

People with Cushing’s disease are much more likely than others to develop blood clots, including rare ones in the brain, even after a pituitary surgery normalizes their cortisol levels, a case report shows.

This finding suggests that patients should be managed with prophylactic (preventive) blood thinners from diagnosis and continuing “for an extended period” after surgery to prevent life-threatening blood clots.

The case report, “Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis after transsphenoidal resection: a rare complication of Cushing disease-associated hypercoagulability,” was published in the journal World Neurosurgery.

Cushing’s syndrome is a hormonal disorder that develops due to prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol (a type of steroid), most often due to a tumor or mass found in the pituitary gland — in which case it is called Cushing’s disease.

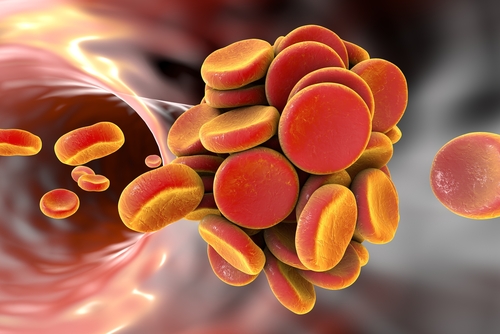

Excess cortisol in circulating blood (hypercortisolism) is associated with a prothrombotic state, meaning patients are more likely to form blood clots due to heightened activation of several clotting factors.

“Hypercortisolism significantly increases the risk of [venous thromboembolism], with some studies reporting a greater than 10-fold elevation in risk compared to a matched population with normal cortisol levels,” researchers explained.

Venous thromboembolism, VTE, is a condition in which a blood clot forms either in the deep veins of the leg, groin or arm (known as deep vein thrombosis), or travels and becomes lodged in the lungs (known as pulmonary embolism). But Cushing’s syndrome patients may also develop other, less reported clotting problems.

In particular, blood clots in the brain’s venous sinuses — the vessels that drain blood from the brain — is a condition called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. It has been described in other forms of Cushing’s syndrome, but not in people with Cushing’s disease.

Now researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and colleagues report what is thought to be the first case of a Cushing’s disease patient who developed cerebral venous sinus thrombosis several weeks after undergoing surgery for his pituitary tumor.

The 18-year-old man arrived at the clinic expressing concerns with delayed puberty, underdeveloped sexual characteristics, and fast weight gain despite an active lifestyle and no changes in his diet.

Blood tests showed elevated cortisol levels that failed to lower with a dexamethasone test, and elevated adrenocorticotropic hormone — the hormone produce by pituitary tumors that act on the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. Both suggested a diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

Imaging scans then revealed a 6 mm tumor in the pituitary gland, consistent with Cushing’s disease.

The man underwent endoscopic transsphenoidal resection to remove the entire tumor, which effectively reduced cortisol to very low levels. He was put on transient steroid hormone replacement therapy, which was tapered upon discharge, five days after surgery.

Despite normal anti-coagulant levels at the time of surgery, the patient was started on blood thinners to prevent blood clots, beginning the day after the operation and continuing up to his discharge. But 25 days after the surgery, he returned to the hospital complaining of an increasingly painful headache. Examination found the pain was caused by cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, with bleeding on both venous sinuses.

While the nature of this complication can vary from person to person, the most common complaint is a diffuse headache that gradually worsens in severity. Seizures are also a known complication of blood clots in brain vessels.

The man again started on blood thinners, but a seizure combined with aspiration led to low oxygen levels that required him to be intubated.

Due to the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation, the patient underwent a tracheostomy (a procedure that allows air to enter the lungs) and gastrostomy (a procedure to let food enter the stomach) for tube placement.

He was discharged 41 days later to a long-term care facility, and, despite several attempts of treatment, died eight months after the initial surgery.

This report underscores that blood clot risks in Cushing’s disease patients are not limited to deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, but in rare instances can include a risk of clots in the brain’s venous sinuses. These patients’ elevated clotting risk also can remain high for “an extended period” after successful surgery, and they likely would benefit from prolonged prophylactic treatment with anti-coagulants.

How long treatment should continue is not clear.

“Previous studies have suggested that the coagulation profile of patients with Cushing syndrome normalizes when measured 12 months after correction of hypercortisolism, but these patients may remain hypercoagulable for an undefined period postoperatively despite becoming adrenally insufficient,” the researchers concluded.