Researchers Establish Cutoff Value for Dexamethasone in Cushing’s Tests

Written by |

While the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome is often based on a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (DST), test results may be affected by differences in the metabolism of the steroid medication, a study found.

The researchers advocated for routine measurement of dexamethasone levels during DST, saying test results should only be considered in individuals with sufficient dexamethasone levels (4.5 nmol/L or higher) after the test, which can help increase the diagnostic accuracy of Cushing’s syndrome.

The study, “Dexamethasone measurement during low‐dose suppression test for suspected hypercortisolism: threshold development with and validation,” was published in the Journal of Endocrinological Investigation.

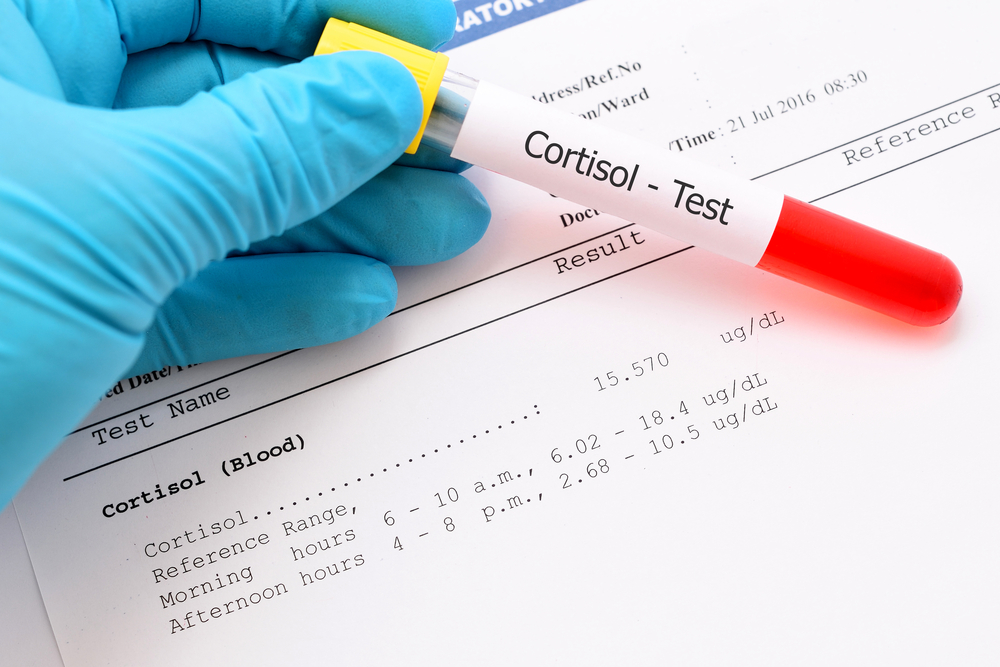

Guidelines for the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome recommend measures of salivary cortisol at night, when its levels should be lower; measures of free cortisol in urine; and an assessment of blood cortisol levels after dexamethasone is administered — which, in normal circumstances, would likely decrease overall cortisol levels.

The first two tests have high diagnostic accuracy, but Cushing’s syndrome patients often have fluctuating cortisol production and secretion, which may compromise the use of the tests.

One of the first choices for measuring excess cortisol is the 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test. This test involves taking a 1 mg dose of a corticosteroid medicine called dexamethasone late at night, and measuring cortisol in circulation early in the morning. If a patient’s morning cortisol levels after this test are above 50 nanomoles per liter, it indicates a positive result for Cushing’s.

The problem with this cutoff value is that despite its high diagnostic sensitivity — meaning no false negatives exist — it has only moderate specificity, with about 40% of positive results turning out to be false.

The variability in dexamethasone metabolism and the presence of certain conditions may change the levels of dexamethasone after a 1 mg DST, which may potentially affect test results. However, there is no known minimum threshold of dexamethasone that needs to be reached for it to carry out an adequate suppression of cortisol.

Researchers in Italy set out to develop and validate a dexamethasone threshold after 1 mg DST. They studied 200 individuals, a first group of 125 who were retrospectively analyzed to determine adequate dexamethasone levels, and a second group of 75 prospectively enrolled patients who were used to validate the findings.

The first group included 16 people with Cushing’s and 110 individuals without the condition. Looking at control patients who achieved adequate cortisol suppression after the dexamethasone test, the researchers determined that dexamethasone levels should be 4.5 nmol/L or higher for the test to be considered valid.

They validated this cutoff in the prospective control group, which confirmed its diagnostic accuracy.

Overall, 94% of patients revealed sufficient dexamethasone levels after 1 mg DST: 92% of those in the retrospective group and 96% in the prospective group.

Serum dexamethasone levels were similar among patients with and without Cushing’s, and the percentage of patients with adequate dexamethasone levels after DST was not different between the groups.

Overall, researchers found that the diagnostic accuracy of the dexamethasone test increased if only patients with sufficient dexamethasone levels after the test were considered.

They also found that the likelihood of a positive diagnosis of Cushing’s was very high (91%) in patients with adequate dexamethasone levels and with cortisol levels higher than 138 nmol/L – well above the established 50 nmol/L threshold.

“Routine measurement of dexamethasone level is feasible in clinical practice, it is independent from patient’s clinical presentation, and is able to increase the diagnostic accuracy of serum cortisol after 1-mg DST for suspected [excess cortisol],” the researchers wrote.