Hormonal Stimulation Improves Tumor Detection in Cushing’s, Study Finds

CLIPAREA l Custom media/Shutterstock

Giving corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) to Cushing’s disease patients helps improve the detection of pituitary tumors on positron emission tomography (PET) scans, increasing the chances of a more successful surgery, a study shows.

The study, “CRH stimulation improves 18F-FDG-PET detection of pituitary adenomas in Cushing’s disease,” was published in the journal Endocrine.

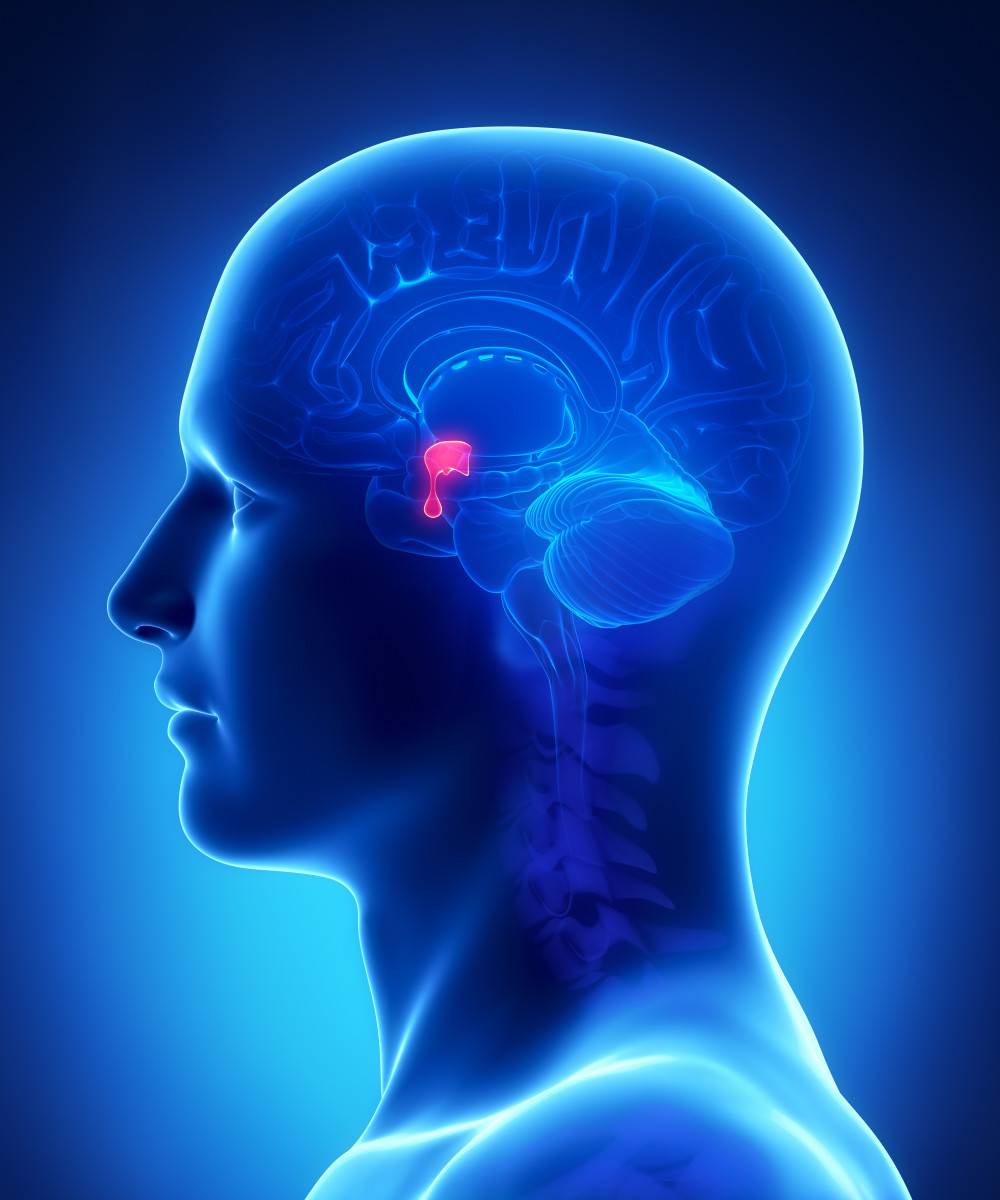

Determining the accurate location of pituitary microadenomas (a small tumor of the pituitary gland) in Cushing’s disease leads to improved clinical remission rates and fewer adverse events after surgical removal of the tumor.

While modern magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tools can consistently detect adenomas in 50% to 80% of cases, some patients have negative MRIs. In these cases, surgeons must extensively explore the pituitary gland, leading to more invasive surgeries.

Therefore, additional imaging strategies are needed to improve detection of microadenomas in Cushing’s disease patients.

Because tumors have an increased uptake of glucose, researchers often use imaging techniques that detect glucose for visualizing tumor location, including those of the pituitary.

Previous studies have shown that a kind of PET imaging called 18F-FDG-PET can detect up to 40% of adenomas causing Cushing’s disease, some even as small as 3 mm. But this is still a low rate of detection.

Interestingly, researchers have shown that CRH leads to a selective glucose uptake into pituitary tumors of Cushing’s patients, thus increasing the visualization of these tumors.

Therefore, researchers conducted an early Phase 1 study (NCT01459237) to evaluate whether use of 18F-FDG-PET with and without ovine CRH (oCRH) stimulation can help improve tumor detection in Cushing’s patients.

The study included 27 patients, mean age 35 years, including four whose disease had already been treated and come back. An MRI scan before surgery detected distinct tumors in 20 patients, but was negative in five and questionable in four.

To confirm whether PET scans with oCRH stimulation would increase detection rates, patients underwent two PET scans, one before and one up to two weeks after oCHR administration.

After oCRH administration, the team reported that the mean amount of radiotracer increased within tumors but not in healthy pituitary tissue, suggesting a selective effect in tumors.

Researchers then took the scans to two neuroradiologists, who qualitatively evaluated the findings. Among the 54 scans read — two for each patient — the neuroradiologists agreed that tumors were visible on 21 scans and not visible on 26 scans. They disagreed on seven scans.

Importantly, oCRH stimulation was associated with a detection of six additional adenomas that were not visible at baseline.

Also, among the five MRI-negative tumors, two were detected on PET imaging, including one that was detected only after oCRH stimulation.

“The results of the current study suggest that oCRH stimulation may lead to increased 18F-FDG uptake, and increased rate of detection of [pituitary tumors in Cushing’s disease],” researchers said. “These results also suggest that some MRI-invisible adenomas may be detectable by oCRH-stimulated FDG-PET imaging.”