Cortisol-secreting Adrenal Incidentalomas More Common than Previously Thought, Study Suggests

Written by |

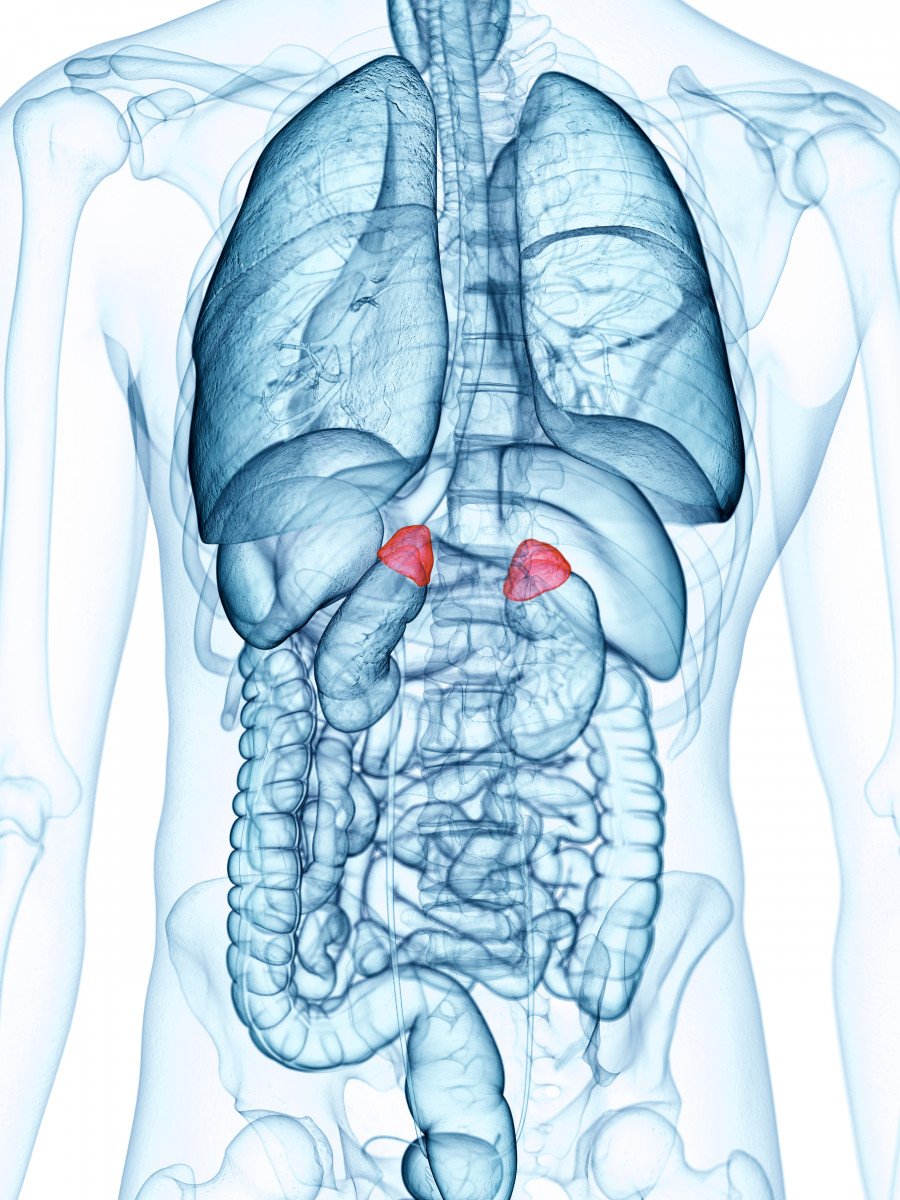

“Functional” adrenal incidentalomas — abnormal masses found by chance in the adrenal glands that are capable of secreting cortisol and causing Cushing’s syndrome — may occur more frequently than previously estimated, a small Japanese study suggests.

These findings suggest that adrenal incidentalomas should be carefully examined, the researchers said.

The study, “Clinical Investigation of Adrenal Incidentalomas in Japanese Patients of the Fukuoka Region with Updated Diagnostic Criteria for Sub-clinical Cushing’s Syndrome,” was published in the journal Internal Medicine.

Adrenal incidentalomas are tumors in the adrenal gland often discovered incidentally during imaging examinations, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, for an unrelated condition. Patients usually have no signs of hormonal excess or obvious underlying malignancy.

Researchers investigated the clinical and endocrine characteristics of adrenal incidentalomas found in 61 patients when they underwent a checkup for another disease. Patients were treated at Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital in Japan.

Two reports had already conducted a similar analysis in Japanese patients, but their criteria for defining subclinical Cushing’s syndrome — when patients have no symptoms of the disease — differed from those recommended by the American Endocrine Society.

In this study, researchers used the updated criteria for subclinical Cushing’s syndrome to define adrenal incidentaloma characteristics, including the clinical factors that may help distinguish patients with “functional” tumors — those capable of secreting hormones and causing symptoms — from those with “nonfunctional” tumors.

The criteria used for identifying subclinical Cushing’s syndrome included cortisol levels higher than 1.8 mcg/dL after a 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test, as well as both lower levels of ACTH in the morning (less than 10 pg/mL) and loss of diurnal serum cortisol rhythm.

Among the 61 adrenal incidentalomas, 23 were in the right adrenal gland, and 38 in the left. All patients were negative for malignant tumors, 13.1% had pheochromocytomas — a rare, usually benign tumor that causes persistent high blood pressure — and 24.6% had primary aldosteronism — excessive production of the hormone aldosterone.

Additionally, using the updated criteria for Cushing’s syndrome and subclinical Cushing’s syndrome, they found 13 patients with cortisol-secreting adenomas — three with Cushing’s syndrome and 10 with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. Twenty-five patients had nonfunctional tumors.

If the researchers had used the old criteria for subclinical Cushing’s syndrome, however, only five patients would have been diagnosed with cortisol-secreting adenomas.

Compared with those with nonfunctional tumors, patients with primary aldosteronism and cortisol-secreting adenomas were much younger and had a significantly higher incidence of hypokalemia, or very low levels of potassium in the blood. Those with pheochromocytomas had much larger tumors and lower body mass index.

Overall, “our study showed a higher ratio of functional tumors among adrenal incidentalomas than past reports,” the researchers wrote.

“Adrenal incidentalomas should be investigated carefully; patients may require hospitalization to facilitate an adequate examination and specialized evaluations from endocrinologists,” they concluded.