Cyclic Cortisol Production May Lead to Misdiagnosis in Cushing’s, Study Finds

Written by |

Increased cortisol secretion may follow a cyclic pattern in patients with adrenal incidentalomas, a phenomenon that may lead to misdiagnosis, a study reports.

Since cyclic subclinical hypercortisolism may increase the risk for heart problems, researchers recommend extended follow-up with repeated tests to measure cortisol levels in these patients.

The study, “Cyclic Subclinical Hypercortisolism: A Previously Unidentified Hypersecretory Form of Adrenal Incidentalomas,” was published in the Journal of Endocrine Society.

Adrenal incidentalomas (AI) are asymptomatic masses in the adrenal glands discovered on an imaging test ordered for a problem unrelated to adrenal disease. While most of these benign tumors are considered non-functioning, meaning they do not produce steroid hormones like cortisol, up to 30% do produce and secrete steroids.

Subclinical Cushing’s syndrome is an asymptomatic condition characterized by mild cortisol excess without the specific signs of Cushing’s syndrome. The long-term exposure to excess cortisol may lead to cardiovascular problems in these patients.

While non-functioning adenomas have been linked with metabolic problems, guidelines say that if excess cortisol is ruled out after the first evaluation, patients no longer need additional follow-up.

However, cortisol secretion can be cyclic in Cushing’s syndrome, meaning that clinicians might not detect excess amounts of cortisol at first and misdiagnose patients.

In an attempt to determine whether cyclic cortisol production is also seen in patients with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome and whether these patients have a higher risk for metabolic complications, researchers in Brazil reviewed the medical records of 251 patients with AI — 186 women, median 60 years old — followed from 2006 to 2017 in a single reference center.

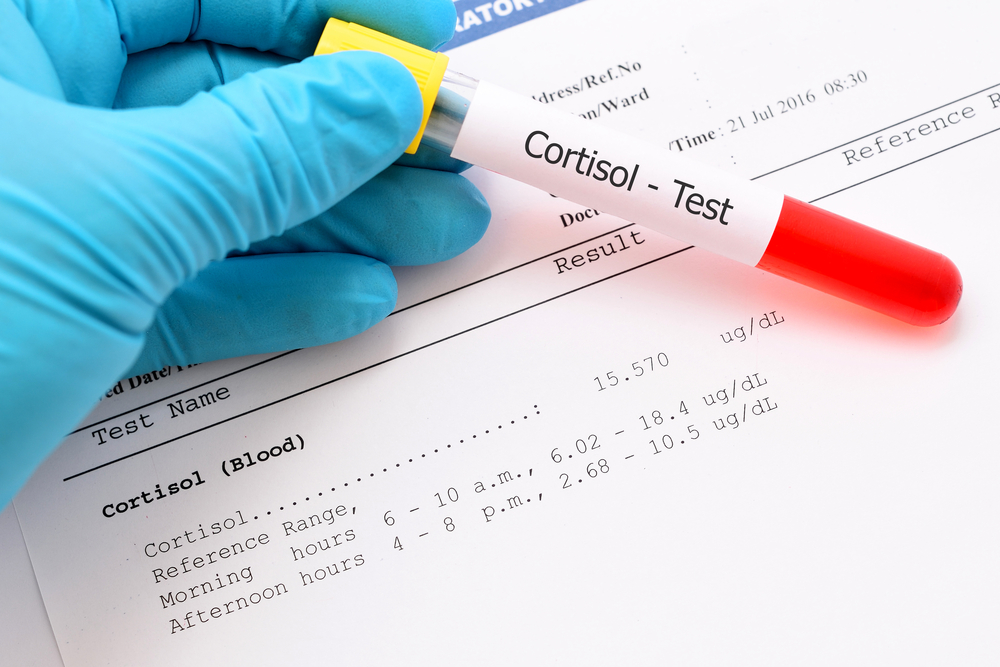

Cortisol levels were measured after a dexamethasone suppression test (DST). Dexamethasone is used to stop the adrenal glands from producing cortisol. In healthy patients, this treatment is expected to reduce cortisol levels, but in patients whose tumors also produce cortisol, the levels often remain elevated.

Patients were diagnosed with cyclic subclinical Cushing’s syndrome if they had at least two normal and two abnormal DST tests.

From the 251 patients, only 44 performed the test at least three times and were included in the analysis. The results showed that 20.4% of patients had a negative DST test and were considered non-functioning adenomas.

An additional 20.4% had elevated cortisol levels in all DST tests and received a diagnosis of sustained subclinical Cushing’s syndrome.

The remaining 59.2% had discordant results in their tests, with 18.3% having at least two positive and two negative test results, matching the criteria for cyclic cortisol production, and 40.9% having only one discordant test, being diagnosed as possibly cyclic subclinical Cushing’s syndrome.

Interestingly, 20 of the 44 patients had a normal cortisol response at their first evaluation. However, 11 of these patients failed to maintain normal responses in subsequent tests, with four receiving a diagnosis of cyclic subclinical Cushing’s syndrome and seven as possibly cyclic subclinical Cushing’s.

Overall, the findings suggest that patients with adrenal incidentalomas should receive extended follow-up with repeated DST tests, helping identify those with cyclic cortisol secretion.

“Lack of recognition of this phenomenon makes follow-up of patients with AI misleading because even cyclic SCH may result in potential cardiovascular risk,” the study concluded.