Study Supports Midnight Salivary Cortisol Test to Diagnose Cushing’s in Chinese Population

Written by |

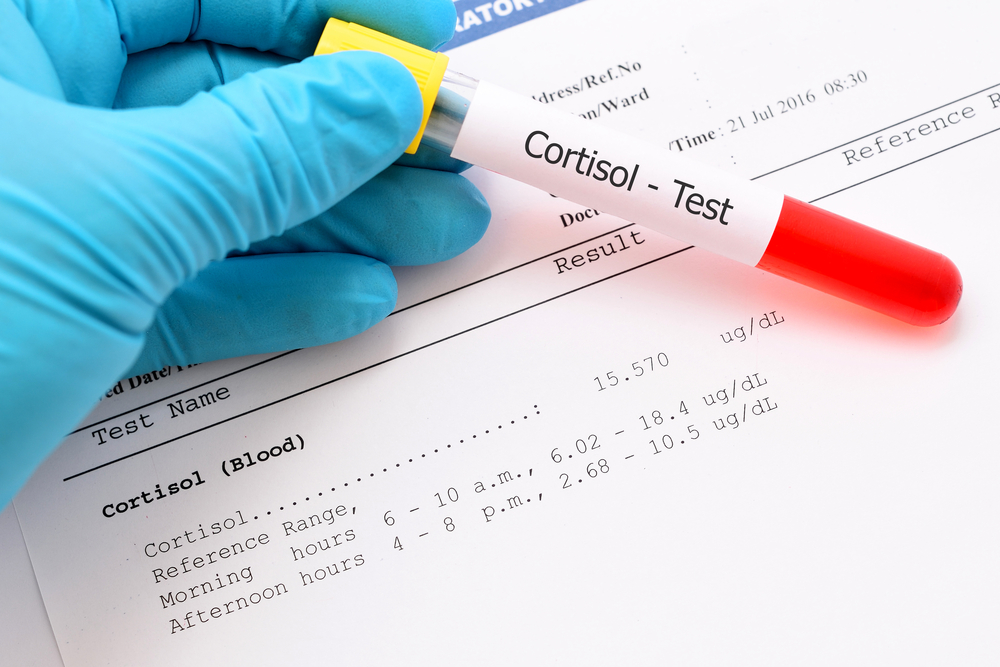

A simple test that measures free cortisol levels in saliva at midnight — called a midnight salivary cortisol test — showed good diagnostic performance for Cushing’s syndrome among a Chinese population, according to a recent study.

The test was better than the standard urine free cortisol levels and may be an alternative for people with end-stage kidney disease, in whom measuring cortisol in urine is challenging.

The study, “Midnight salivary cortisol for the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in a Chinese population,” was published in Singapore Medical Journal.

Cushing’s syndrome, defined by excess cortisol levels, is normally diagnosed by measuring the amount of cortisol in bodily fluids.

Traditionally, urine free cortisol has been the test of choice, but this method is subject to complications ranging from improper collection to metabolic differences, and its use is limited in people with poor kidney function.

Midnight salivary cortisol is a test that takes into account the normal fluctuation of cortisol levels in bodily fluids. Cortisol peaks in the morning and declines throughout the day, reaching its lowest levels at midnight. In Cushing’s patients, however, this variation ceases to exist and cortisol remains elevated throughout the day.

Midnight salivary cortisol was first proposed in the 1980s as a noninvasive way to measure cortisol levels, but its efficacy and cutoff value for Cushing’s disease in the Chinese population remained unclear.

Researchers examined midnight salivary cortisol, urine free cortisol, and midnight serum cortisol in Chinese patients suspected of having Cushing’s syndrome and in healthy volunteers. These measurements were then combined with imaging studies to make a diagnosis.

Overall, the study included 29 patients with Cushing’s disease, and 19 patients with Cushing’s syndrome — 15 caused by an adrenal mass and four caused by an ACTH-producing tumor outside the pituitary. Also, 13 patients excluded from the suspected Cushing’s group were used as controls and 21 healthy volunteers were considered the “normal” group.

The team found that the mean midnight salivary cortisol was significantly higher in the Cushing’s group compared to both control and normal subjects. Urine free cortisol and midnight serum cortisol were also significantly higher than those found in the control group, but not the normal group.

The optimal cutoff value of midnight salivary cortisol for diagnosing Cushing’s was 1.7 ng/mL, which had a sensitivity of 98% — only 2% are false negatives — and a specificity of 100% — no false positives.

While midnight salivary cortisol levels correlated with urine free cortisol and midnight serum cortisol — suggesting that all of them can be useful diagnostic markers for Cushing’s — the accuracy of midnight salivary cortisol was better than the other two measures.

Notably, in one patient with a benign adrenal mass and impaired kidney function, urine free cortisol failed to reach the necessary threshold for a Cushing’s diagnosis, but midnight salivary and serum cortisol levels both confirmed the diagnosis, highlighting how midnight salivary cortisol could be a preferable diagnostic method over urine free cortisol.

“MSC is a simple and non-invasive tool that does not require hospitalization. Our results confirmed the accuracy and reliability of [midnight salivary cortisol] as a diagnostic test for [Cushing’s syndrome] for the Chinese population,” the investigators said.

The team also noted that its study is limited: the sample size was quite small, and Cushing’s patients tended to be older than controls, which may have skewed the results. Larger studies will be needed to validate these results in the future.