‘Mini Pituitary Tumors’ May Help Personalized Medicine, Study Says

Patient-derived organoids can serve as research models and to tailor treatment

Written by |

“Mini pituitary tumors” derived from patients, including those with Cushing’s disease, mimic several features of the individual’s tumor, including response to treatments, a study shows.

These pituitary tumor-like organoids can serve as models for studies of the underlying molecular mechanisms of Cushing’s disease and to screen for the most effective treatments for each patient, the researchers noted.

This will contribute to developing “effective personalized medicine for [Cushing’s disease] patients,” they wrote.

The study, “Development of Human Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumor Organoids to Facilitate Effective Targeted Treatments of Cushing’s Disease,” was published in the journal Cells.

Disease recurrence is common after transsphenoidal surgery

Cushing’s disease is commonly caused by a benign tumor in the brain’s pituitary gland that overproduces the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH signals the adrenal glands sitting atop the kidneys to produce and release a steroid hormone called cortisol.

Given its role in several bodily processes, excess levels of cortisol lead to the wide variety of physical, hormonal, and psychological symptoms of Cushing’s.

The first line of treatment consists of transsphenoidal surgery — a minimally invasive surgery performed through the nose — to remove the pituitary tumor. Still, up to half of the cases are reported to experience disease recurrence after surgery.

Medications are considered when surgery is not possible or is ineffective, or when recurrence occurs after initial surgical remission. However, these treatments have reduced efficacy and tolerability, and the disease remains without effective long-term remission in 30% of Cushing’s patients.

“Overall, existing medical therapies remain suboptimal, with negative impact on health and quality of life, including considerable risk of therapy resistance and tumor recurrence,” the researchers wrote.

This indicates the need to develop effective pharmacological therapies that target pituitary tumors to lower cortisol levels in the body. One major limitation has been the lack of an adequate preclinical model that replicates the specific microenvironment of pituitary tumors.

Collectively, we have developed a relevant human [lab-dish] approach to potentially advance our knowledge as well as our approach to studies in the field of pituitary tumor research

U.S. researchers develop 3D patient-derived organoids

To address this, a team of researchers in the U.S. developed patient-derived pituitary tumor-like organoids. Organoids are three-dimensional cellular structures that better mimic diseased tissue and are thus considered a valuable tool to predict a therapy’s clinical benefit.

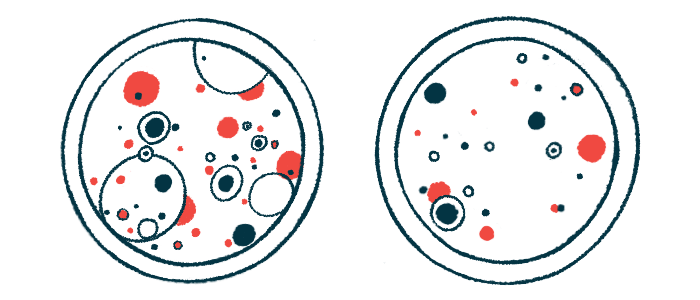

These “mini pituitary tumors” were first generated from cells of different types of pituitary tumors that were removed from 35 patients (12 with Cushing’s disease) by transsphenoidal surgery.

The resulting organoids were structurally diverse across tumor subtypes and individual patients. As expected, the “mini pituitary tumors” generated from Cushing’s patients produced the highest levels of ACTH.

Moreover, the organoids recapitulated much of the patient’s tumor characteristics. This was observed by comparing the levels of tumor-specific proteins in the organoids and the original tumors.

Also, about 80% of the genetic variants observed in the tumors of Cushing’s patients were retained in the corresponding organoids.

A large-scale drug screening assay revealed that the sensitivity of the “mini pituitary tumors” to a range of 83 medications reflected each patient-specific response in each tumor subtype.

Cellular sensitivity or resistance to therapies was determined by assessing cell death; higher cell death meant sensitivity to a specific medication, and lower cell death meant resistance.

“These data clearly demonstrate that the inherent patient difference to drug response that is often observed among [Cushing’s disease] patients is reflected in the organoid culture,” the team wrote.

This study is “the first report of the use of [human pituitary tumor organoids] for drug screening,” the researchers wrote, and “may be an approach that will provide functional data revealing actionable treatment options for each patient.”

Medications showing similar responses were further investigated for their mode of action based on target genes. The genes identified were associated with cell growth and maturation, and nerve cell function.

“These data reveal potential therapeutic pathways for [Cushing’s disease] patients,” the researchers wrote.

Organoids also created from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells

The team then created pituitary organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from the blood of two Cushing’s patients and one healthy donor. iPSCs are generated from fully matured cells that are reprogrammed back to a stem cell-like state, where they can give rise to almost every type of human cell.

The iPSC-derived organoids from Cushing’s patients also retained characteristics similar to the tumor tissue.

These also “revealed the existence of cell populations that potentially contribute to the support of [pituitary tumor] growth and disease progression, as well as an expansion of stem and progenitor cells that may be the targets for tumor recurrence,” the team wrote.

“Collectively, we have developed a relevant human [lab-dish] approach to potentially advance our knowledge as well as our approach to studies in the field of pituitary tumor research,” the researchers concluded.

Both types of organoids may contribute to the study of the underlying mechanisms of pituitary tumors and Cushing’s disease, as well as to the development of tailored patient therapies.