Tracking Cortisol After Cushing’s Disease Surgery Is Good Way to Predict Remission, Study Finds

Written by |

Measuring blood serum cortisol levels several times a day after pituitary tumor surgery for Cushing’s disease can help doctors predict whether the operation eliminated the disorder, a study reports.

The hormone measurements are also valuable for determining if a patient needs a second surgery, which improves the chance that the disease will go into remission.

The hallmark of Cushing’s disease is the production of too much cortisol. That problem leads to symptoms such as high sugar levels, high blood pressure, muscle weakness, weight gain, brittle bones and kidney stones.

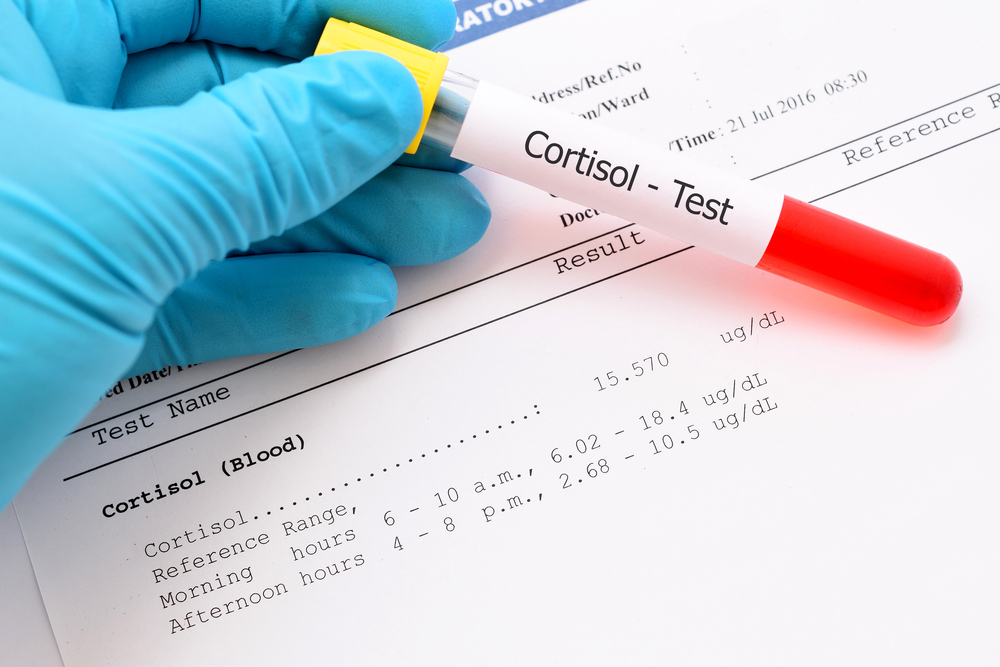

Researchers at the Swedish Neuroscience Institute in Seattle and the University of Washington noted that a person’s cortisol levels can vary widely after surgery, depending on when they are measured. So they called on doctors to measure cortisol every six hours after an operation.

Their study, published in the Journal of Neurosurgery, is titled “Dynamics of postoperative serum cortisol after transsphenoidal surgery for Cushing’s disease: implications for immediate reoperation and remission.”

Many doctors use serum cortisol levels to get an idea of whether pituitary tumor surgery for Cushing’s disease is successful. Doctors also agree that a second surgery can improve the chance of the disease going into remission.

But studies supporting these notions have been poorly designed, the Seattle researchers noted. Some measured cortisol only once or twice. Others included patients who had received corticosteroids to replace cortisol. Still others failed to relate cortisol levels with remission.

The team decided to follow 89 patients who had surgery at the institute, where cortisol levels are measured every six hours for the first 72 hours after surgery.

Although patients’ cortisol levels varied widely, those who had lower levels every time that measurements were taken were more likely to achieve remission. Patients achieve their lowest cortisol levels at different times, with the range being 12 to 66 hours after surgery. This showed that a single measurement is not enough to base additional treatment decisions on, the researchers said.

The team also established that patients with the lowest cortisol levels after surgery were less likely to have a very late relapse.

A late relapse occurred in 10 percent of 63 patients, with the average time of the recurrence coming at 44 months.

A finding that went against conventional wisdom was that patients with a single surgery had similar remission and recurrence rates as those with a second surgery.

“Immediate second surgery using postoperative cortisol criteria is highly effective in improving remission rates, and is safe,” the team wrote, but admitted that a second surgery more often gave rise to a too low production of cortisol.

“Postoperative serum cortisol [measurements] within 72 hours can predict subsequent remission with excellent accuracy,” they concluded.