ACTH Suppression Test Predicts Remission After Pituitary Tumor Removal, Study Shows

Written by |

A test using betamethasone — a corticosteroid that causes the pituitary gland to stop producing ACTH – can accurately predict short- and long-term remission in Cushing’s disease patients who have had pituitary surgery, a retrospective study reports.

The research, “An early post-operative ACTH suppression test can safely predict short- and long-term remission after surgery of Cushing’s disease,” was published in Pituitary. The work was developed at the Skåne University Hospital, part of Lund University in Sweden.

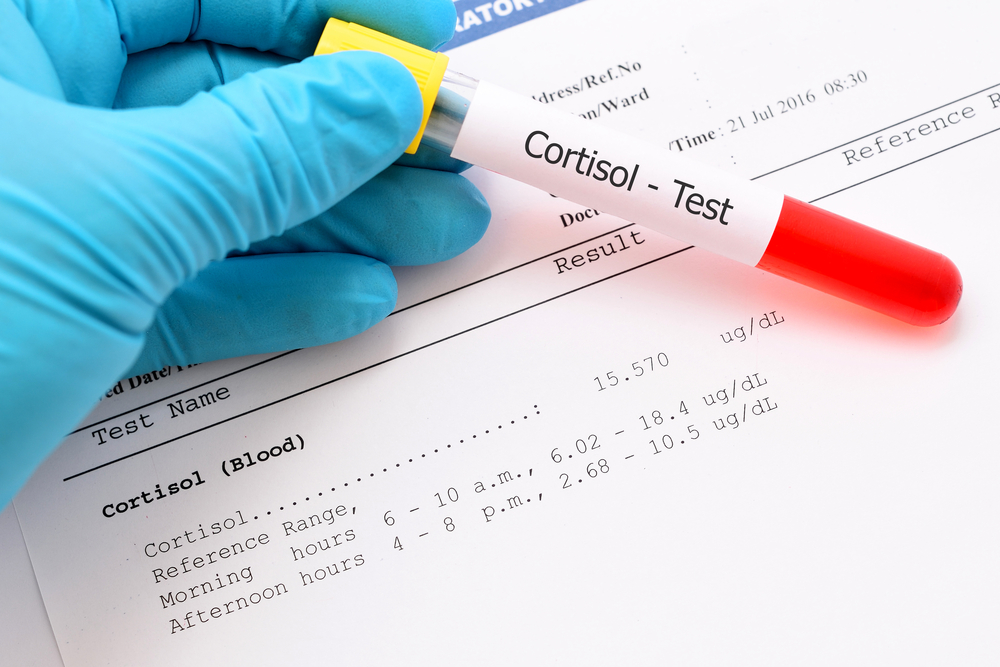

Cushing’s disease is caused by a benign tumor (adenoma) in the pituitary gland that produces excess adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which acts on the adrenal glands, making them produce cortisol. The excess cortisol causes weight gain, easy bruising, and muscular weakness.

Currently, the treatment of choice for Cushing’s disease is surgical removal of the pituitary adenoma.

After surgery, glucocorticoid levels drop dramatically and may result in insufficient cortisol production, a life-threatening situation. Because of this, patients who have had a tumor removed often require glucocorticoid replacement therapy.

Remission after surgery is seen in 43-95% of cases, depending on tumor size, preoperative tumor detection via imaging, and surgeons’ experience.

“However, there is no consensus on what laboratory assays and biochemical thresholds should be used in determining or predicting remission over time,” researchers said.

At the hospital, on day two after surgery, doctors performed a 48-hour suppression test with betamethasone (2 mg per day) for an early assessment of the surgery’s effect.

Betamethasone significantly decreases ACTH secretion, reducing cortisol levels. In the complete removal of an adenoma, cortisol levels should remain low; if some tumor tissue is left behind, ACTH is continuously produced and cortisol levels remain elevated.

“After completion of the test, patients are deemed in remission and given continued glucocorticoid substitution, or considered uncured and thus not in need of substitution,” researchers said.

With this in mind, scientists looked into whether the betamethasone suppression test could predict short- and long-term remission after surgery. They also studied what would be the cut-off levels of the test-related laboratory analysis.

They analyzed medical records of patients who had undergone pituitary surgery between November 1998 and December 2011, allowing for at least five years of follow-up examinations.

A 48-hour suppression test — oral betamethasone administered on the second or third post-surgery — was given to 28 patients after a total of 45 pituitary tumor removals (primary surgeries or re-operations).

The team measured levels of cortisol and ACTH at 24 and 48 hours later. Urine was collected at 24 hours later to measure the amount of cortisol it contained.

Twelve patients remained in remission for five years or longer after one surgery, but 13 others required additional surgeries. Three patients were not candidates for further procedures.

Most, 57 percent, of these patients went into remission for five or more years.

Results showed that 24-hour cortisol levels could accurately predict remission, both in the short term (three months) and in the long term (five years). The cut-off level was established as 107 nmol/L (nanomoles per liter) for short-term analysis and 49 nmol/L for long-term assessment.

ACTH levels and urinary-free cortisol did not improve diagnostic accuracy.

“The present data supports that an early suppression test can be helpful in this assessment in predicting remission over time with high accuracy without the risk of adrenal crisis,” researchers concluded.