Bone problems common in Cushing’s, but care varies across Europe: Study

Researchers cite urgent need for clearer guidelines to help improve care

Written by |

Bone complications are frequent in people with Cushing’s syndrome, including those with Cushing’s disease, but are not consistently assessed or treated across Europe, according to a large study.

The findings, based on data from nearly 1,700 patients, showed that osteoporosis — a condition marked by fragile bones — and fractures were frequent. Yet, only a minority of patients underwent bone testing at diagnosis, and bone health was not consistently reassessed after Cushing’s treatment. The study also revealed considerable variation across European centers in the evaluation and management of bone disease.

“Our study has demonstrated that around 20% of patients with active [Cushing’s syndrome] experienced bone complications at initial evaluation,” researchers wrote. They added that the “significant heterogeneity regarding bone disease evaluation and management across European centers” highlights the urgent need for clearer guidelines to improve and standardize care.

The study, “Prevalence, risk factors and management of bone complications in Cushing`s syndrome across Europe. Data from the European Registry on Cushing’s syndrome (ERCUSYN),” was published in the journal Annales d’Endocrinologie.

Cortisol excess can weaken bones

Cushing’s syndrome is caused by long-term exposure to high levels of the hormone cortisol, most often due to tumors in the adrenal gland or, in the case of Cushing’s disease, the pituitary gland.

Cortisol excess can weaken bones by slowing new bone formation while increasing bone breakdown, which can lead to osteoporosis and raise fracture risk. Studies suggest that 22% to 56% of people with Cushing’s develop osteoporosis and 16% to 76% experience fractures.

Yet important questions remain about how often bone complications occur and “the most effective strategies that should be adopted to diagnose, monitor, and treat” them in clinical practice, the researchers noted.

To address this gap, the team analyzed data from 1,682 people with Cushing’s syndrome included in the European Registry on Cushing’s Syndrome (ERCUSYN), which collects real-world clinical information on the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of the condition across Europe. Participants included in the analysis were enrolled at 60 centers in 26 European countries between 2000 and 2021.

Most patients were women (80%), and the mean age at diagnosis was 44.3 years. Among them, 73% had Cushing’s disease and 27% had adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Patients with adrenal disease were older on average (47 years vs. 43 years). The median delay to Cushing’s diagnosis was two years. Patients were followed for a median of 44.1 months after treatment, and 79% were in remission during follow-up, meaning they had no signs of active disease.

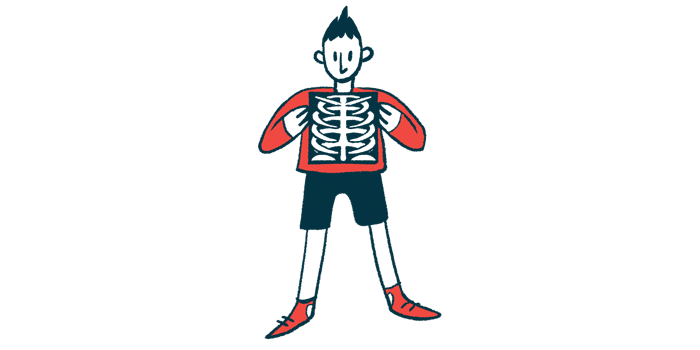

Bone health was not routinely assessed at diagnosis. A bone density scan (DXA) was performed in 45% of patients. Among those tested, 21% had spinal osteoporosis, and 13% had hip osteoporosis.

Follow-up bone monitoring after Cushing’s treatment was inconsistent

Spinal osteoporosis was more common in men, in patients with lower body mass index (BMI) — a measure of body fat based on weight and height — and in those reporting muscle weakness. Older age was also linked to a higher risk, while higher BMI appeared protective. Patients who had fractures were more than three times as likely to have spinal osteoporosis.

X-rays to check for fractures were performed in 29% of patients. Of those, 18% had at least one fracture, most often in the spine. Fractures were also more frequent in men. Patients reporting muscle weakness were about six times more likely to have fractures, and those with hip osteoporosis had a fivefold higher chance of fractures.

Follow-up bone monitoring after Cushing’s treatment was also inconsistent. Only 39% of patients with an initial DXA scan and 17% of those with an initial X-ray had follow-up imaging.

Due to the relatively great prevalence of bone complications in [Cushing’s syndrome], regular bone assessment should be performed in all patients while guidelines for optimal management in this setting are highly needed.

At follow-up, improvements in bone density were observed in 33% of patients at the spine and 27% at the hip. However, some patients experienced worsening bone loss (6% at the spine and 10% at the hip), while others developed osteoporosis (5% at the spine and 6% at the hip). New fractures were detected in 11% of patients, and all but one were in remission.

To better understand how bone health is managed in clinical practice, the researchers also surveyed centers participating in ERCUSYN. Among 60 invited to respond to a 13-question survey, 39 centers responded.

Although most doctors (87%) reported that bone health should be evaluated at diagnosis and after treatment, registry data showed this was not done consistently. Approaches to follow-up testing and treatment also varied widely among centers, with differences in how soon and how often bone scans were performed after treatment, and in when osteoporosis medications were started.

“Due to the relatively great prevalence of bone complications in [Cushing’s syndrome], regular bone assessment should be performed in all patients while guidelines for optimal management in this setting are highly needed,” the researchers concluded.