Cushing’s Patients with Excess Prolactin Respond Well to Dopamine Agonists, Report Suggests

Written by |

In some rare cases, Cushing’s disease patients have a benign pituitary tumor that produces several pituitary hormones in excess, rather than just the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). When these tumors also produce prolactin, they can be treated with dopamine agonists as an alternative to surgery, a case report suggests.

The study, “Dopamine agonist-responsive Cushing’s disease,” was published in the journal BMJ Case Reports.

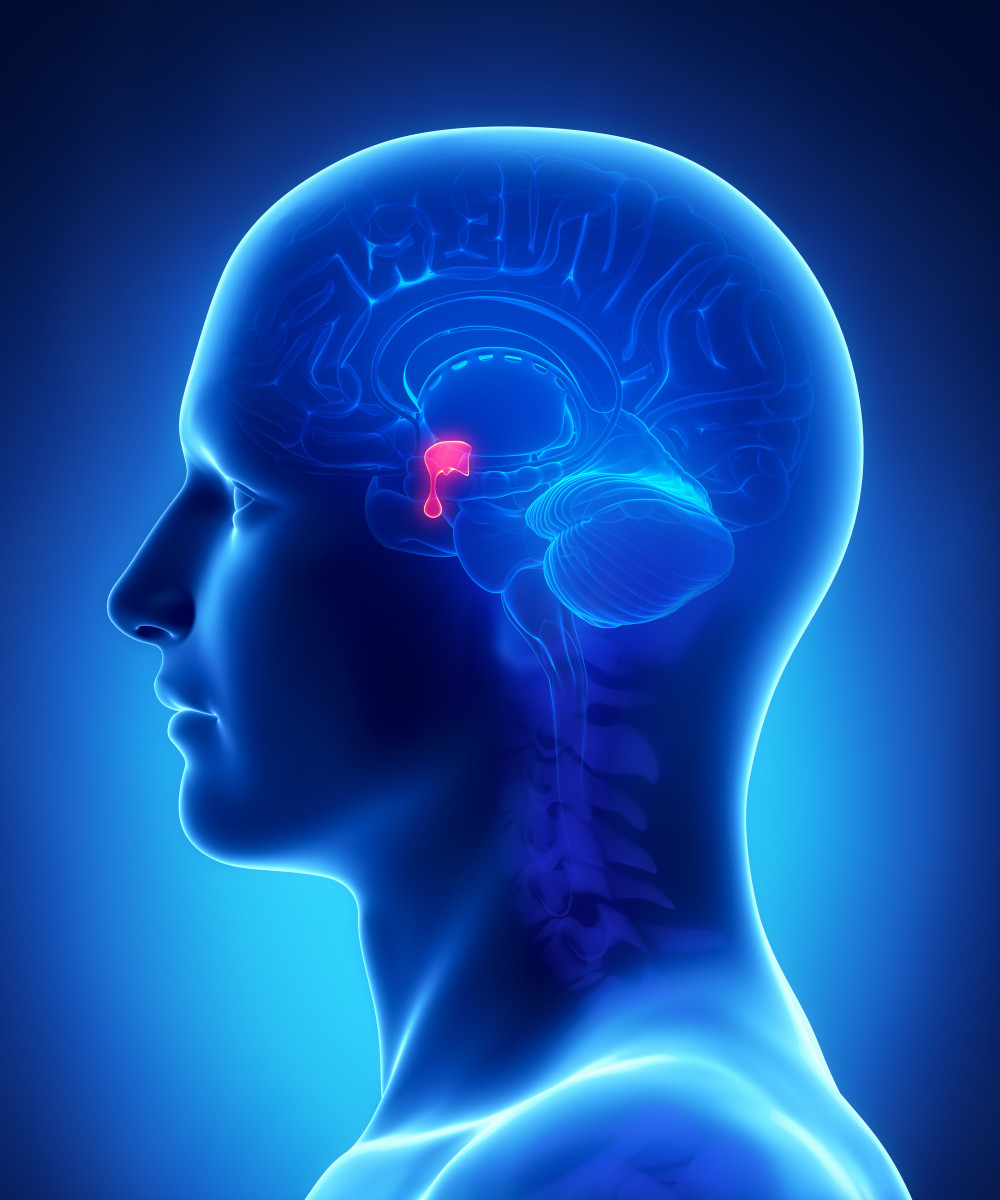

The pituitary gland secretes different types of hormones that control the function of other glands such as the thyroid, the adrenal glands, and the testicles and ovaries.

When a pituitary tumor arises, it usually causes an imbalance in the production of pituitary hormones. Most tumors secrete only one type of hormone, but in rare cases, they can produce a mix of hormones.

Researchers in Switzerland described the case of a 47-year-old Caucasian man with no family history of hormonal disorders who developed a benign tumor in his pituitary gland that produced excessive levels of ACTH, prolactin, and growth hormone.

By the time the patient came to the hospital, he had already been diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome. He also had diabetes, which was difficult to manage, had noticed abnormal weight gain over the last two years, and had high blood pressure and sleep apnea (difficulty in breathing while asleep).

A first examination revealed that the man had reduced strength in the legs, low libido, lack of concentration, and difficulty seeing on one side.

Blood tests confirmed that the patient had Cushing’s syndrome caused by excess ACTH, but he also showed very high levels of prolactin and moderately high levels of growth hormone. He also had testicle malfunction and hypothyroidism — when the thyroid does not secrete enough hormones.

By performing imaging tests, doctors discovered a 3.6-cm tumor in his pituitary gland. They speculated that the tumor produced high levels of ACTH and prolactin and some growth hormone.

Pituitary tumors that release prolactin express dopamine receptors and tend to respond well to treatment with dopamine agonists; this is not the case for tumors that produce ACTH only.

The doctors decided to evaluate the patient’s response to a dopamine agonist before attempting surgery and found that he responded very well. The prolactin levels started to decrease after one week and normalized at approximately eight months. The tumor volume decreased to almost a third of its original volume.

The treatment also caused the remission of Cushing’s disease, with cortisol levels normalizing after three weeks of treatment. After five weeks, however, the patient started to feel weak again because of reduced cortisol levels caused by the treatment.

The patient received a replacement therapy (hydrocortisone) for approximately five months, which regulated cortisol levels and made him feel better.

Dopamine agonist treatment also helped the man lose about 37.5 pounds, which, together with the reduction in cortisol levels, made his diabetes easier to manage. The testicular function improved without any hormone treatment, and his hypothyroidism and visual problems also disappeared.

Because all the symptoms lessened after tumor reduction, the doctors believe that the primary tumor caused the abnormalities in the function of other glands (testicles and thyroid).

“It is important to mention that guidelines do not offer much help in managing very rare cases of multiple pituitary hormone secretions. It is best to decide on a case-to-case basis, relying on treatment response, as in our case,” the researchers said.

“In a rare case of combined ACTH-producing and prolactin-producing tumor, medical treatment with a dopamine agonist may be a good alternative to surgery,” they concluded.