Removal of 1 affected adrenal gland effective in some Cushing’s cases

Half of patients achieved disease remission 6 months after surgery: Study

Written by |

Surgical removal of one cancerous adrenal gland resulted in disease remission after six months in nearly half of people with Cushing’s syndrome due to tumors in both adrenal glands — a condition known as primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia, or PBMAH.

That’s according to data from a study in China that also showed that rates of disease remission dropped to about one-third with longer follow-ups of up to three years. Among responders, surgery also significantly lessened high blood pressure, or hypertension, and bone complications associated with PBMAH.

Moreover, patients’ initial blood cortisol levels and response to a low-dose dexamethasone test, commonly used to diagnose Cushing’s, could predict an individual’s long-term treatment response after such surgery, the researchers noted.

“We innovatively propose that [certain measures of patient cortisol levels at the study’s start] are predictors of persistent hypercortisolism [high cortisol levels] on long-term follow-up in patients with PBMAH treated with [surgical removal of one adrenal gland],” the team wrote.

The study, “Long-term outcome of unilateral adrenalectomy for primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia,” was published in the journal Endocrine.

Removal of 1 adrenal gland became preferred approach in 1990s

Cushing’s syndrome is characterized by high blood levels of the hormone cortisol, which is known as hypercortisolism. Cushing’s disease, its most common form, is caused by a tumor in the brain’s pituitary gland that excessively produces the adrenocorticotropic hormone, or ACTH. That, in turn, boosts cortisol production by the adrenal glands, a pair of glands on top of the kidneys.

Less frequently, Cushing’s may be caused by conditions directly affecting the adrenal glands. PBMAH, marked by large nodules in both adrenal glands that lead to higher production and release of cortisol, is estimated to account for about 5% of Cushing’s syndrome cases.

Surgical removal of both adrenal glands had long been the standard treatment for PBMAH, as it was associated with efficient control of cortisol levels. However, the surgery’s associated adrenal function insufficiency meant that patients had to undergo lifelong hormonal replacement therapy, which “carries risks of complications and mortality,” or death, the researchers wrote.

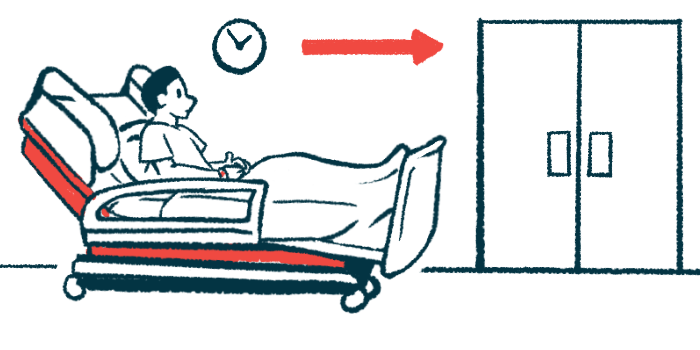

To overcome this, unilateral adrenalectomy, or surgery to remove only one of the adrenal glands, became the preferred approach for treating BMAH, beginning in the late 1990s.

“However, limited research exists on its postoperative efficacy and prognostic predictors,” the researchers wrote.

Now, researchers with The Third Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital in Beijing analyzed data from 45 PBMAH patients who underwent unilateral adrenalectomy between 2004 and 2022 and were followed for at least three months after the surgery.

More than half of the patients, who had a mean age of 51.6, were women (60%). A total of 53.3% had Cushing’s symptoms at diagnosis. Most patients had hypertension (82.2%) and obesity (82.2%), followed by issues in regulating blood sugar levels (60%), and osteoporosis or osteopenia (37.8%) — conditions characterized by loss of bone mass, making bones weak and brittle.

Disease remission was classified as adrenal insufficiency or the normalization of a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test. In normal conditions, administration of a low dose of the corticosteroid dexamethasone results in a reduction in blood cortisol levels, but in Cushing’s patients, this has no effect on cortisol levels.

Researchers propose way of predicting patient outcomes after surgery

Within six months, 22 patients (48.9%) achieved initial disease remission, the results showed. Before surgery, the responders were less likely to have symptoms, had higher ACTH levels, and showed lower 24-hour urinary-free cortisol levels than those who did not experience disease remission.

A total of 25 patients were followed over the long term, for a mean of about three years. More than half of these patients (52%) had achieved remission within the first six months, and nearly one-third (32%) were in remission at their last evaluation.

None of the patients in the long-term remission group had Cushing’s symptoms before the surgery, compared with 82.4% of those with persistent high cortisol. Also, responders had smaller adrenal nodules.

Conversely, patients in whom high cortisol levels persisted after surgery had higher blood and urine cortisol levels and a lower response to the dexamethasone test before the surgery.

Further analyses showed that patients with 24-hour urinary cortisol levels up to twice the upper limit of normal (ULN) before surgery were significantly more likely to achieve long-term remission than those with higher levels (50% vs. 9%).

Also, patients experiencing a reduction of cortisol levels in response to the dexamethasone test were more likely to achieve disease remission after surgery than those who did not respond to the test (66.7% vs. 6%).

These findings highlight that higher 24-hour urinary cortisol levels and a negative response to the low-dose dexamethasone test may help predict which patients will continue to show persistently high cortisol levels in the long term after the removal of one adrenal.

Regarding the surgery’s effect on co-existing conditions, patients achieving disease remission were less likely to have hypertension and osteoporosis after the surgery compared with those showing persistently high cortisol levels.

Moreover, “hypertension decreased with [disease] remission, whereas osteoporosis worsened with persistent hypercortisolism,” the team wrote.