Signifor Lowers Tumor Volume in Cushing’s Patients, Analysis of Phase 3 Trial Shows

Written by |

One year of treatment with under-the-skin Signifor (pasireotide) lessens tumor volume in many Cushing’s disease patients for whom surgery has failed or is not an option, a post-hoc analysis of a Phase 3 clinical trial shows.

Signifor was found to normalize urinary cortisol levels and ease symptoms of the disease — patients in the trial lost both weight and excessive body hair — making it an attractive treatment option.

The study, “Pasireotide treatment significantly reduces tumor volume in patients with Cushing’s disease: results from a Phase 3 study,” was published in the journal Pituitary.

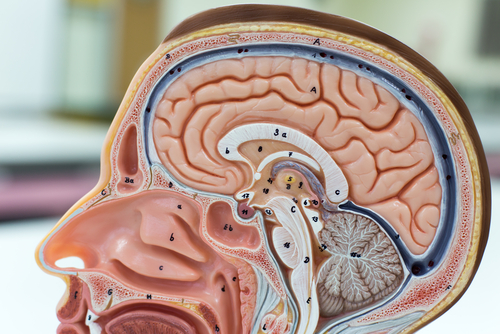

Cushing’s disease is caused by excessive production of the adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) by the pituitary tumor, leading to a chronic increase in cortisol production by the adrenal glands.

Surgery to remove the pituitary tumor is the recommended treatment for people with the condition, but remission rates are low among those with recurrent or persistent Cushing’s disease, and some experience pituitary problems, such as low levels of pituitary hormones.

Signifor, marketed by Recordati, was the first medication approved for adults with Cushing’s disease who are not eligible for surgery or have experienced relapses after surgery. It is an analogue of the hormone somatostatin, and works by activating its receptors in the pituitary tumor and decreasing the production of ACTH and cortisol.

The therapy was approved based on findings from the Phase 3 B2305 trial (NCT00434148), which tested two Signifor doses (600 micrograms and 900 mcg), both given under the skin and twice daily, in 162 patients.

Patients were randomly assigned to one of these two doses for six months, after which they entered an open-label phase, with possible dose adjustments, lasting another six months. They then had the option of entering an open-label extension of the trial.

The study’s main goal was to determine the proportion of patients whose cortisol levels returned to normal after six months without increasing the dose. Of the patients, 15% of those receiving 600 mcg, and 26% of those on 900 mcg, met that goal.

Among the secondary measures studied, signs and symptoms of the condition were also alleviated after six and 12 months, including decreases in blood pressure, fat molecules, weight, and improvements in health-related quality of life. In some patients, fat deposits were also smaller.

Findings also showed reductions in tumor volume, particularly among those receiving the higher dose, who experienced an average 44% decrease in tumor volume after six months.

This led an international team of researchers to examine if changes in tumor volume were associated with tumor size at the study’s start, and whether the effects were dependent on urinary cortisol control.

The analysis included the 53 patients who had measurable tumor volume at the time of enrollment and after six months of treatment. Of these, 32 also had available data for the 12th month.

Researchers found that the proportion of patients whose tumor volumes shrank increased both with the dose used and with time. At six months, 44% of patients receiving the 600 mcg dose and 75% of patients on the 900 mcg dose had some tumor reduction. Decreases of 50% or more were observed in 8% of the patients receiving 600 mcg, and in 21% of those on 900 mcg.

After 12 months, the rate of tumor reduction increased to 50% for those receiving 600 mcg, and 89% for the 900 mcg dose group. Among those with tumor regression at six months, 67% taking 600 mcg and 81% taking 900 mcg continued to see their tumor volumes shrink through 12 months. Yet only half of patients with tumor reductions in the higher-dose group achieved full control of urinary cortisol levels; the remainder didn’t have partial or full normalization, suggesting that tumor reduction is not dependent on cortisol control.

In the 600 mcg dose group, people with smaller tumors (0.2 cm3 or smaller) at the study’s start were more likely to experience tumor reductions than those with larger tumors (greater than 0.2 cm3). This association was not seen in patients receiving the higher dose.

“The results of the current study demonstrate a measurable decrease in MRI-detectable pituitary tumor volume in a majority of patients with [Cushing’s disease] who were treated with pasireotide 900 mcg (75% at month 6; 89% at month 12), but in a smaller percentage of patients treated with pasireotide 600 mcg (44% at month 6; 50% at month 12),” the researchers wrote.

“Pasireotide is an attractive option for these patients, especially in cases in which patients cannot undergo transsphenoidal surgery or do not respond to surgical management of disease,” they said.