Achieving disease remission may mean a longer life in Cushing’s

Lower mortality for those in remission - no matter how long it takes

Written by |

People with Cushing’s disease who achieve remission — no matter how long that takes — are more likely to live a longer life than are patients who have active disease, a 20-year study found.

Achieving remission, which is when symptoms ease or disappear, was linked to fewer deaths, also known as a lower mortality rate, among Cushing’s patients during the study’s two decade time period.

“At the last follow-up examination the [Cushing’s disease] patients in remission had a mortality rate that was comparable to that of the general population regardless of the number of treatments needed to achieve remission,” the researchers wrote.

Receiving a diagnosis at a younger age also increased survival, the study found.

The study, “Complications and mortality of Cushing’s disease: report on data collected over a 20-year period at a referral centre,” was published in the journal Pituitary.

Investigating disease treatment, remission over 20 years

Cushing’s occurs when the adrenal glands, which sit atop the kidneys, produce too much of a hormone called cortisol, resulting in a range of symptoms from weight gain and a buildup of fat to easily bruising skin and stretch marks. Some of the disease’s symptoms are systemic, meaning they can affect the entire body.

Such symptoms can lead to serious complications, which may be linked to a greater chance of dying. Indeed, researchers note that patients have a high mortality rate, “for the most part linked to cardiovascular (CV) events.”

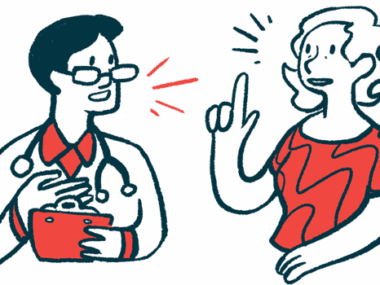

Thus, the main goal for doctors treating Cushing’s patients is to achieve remission, which means controlling the disease. However, it’s not known if treatment also increases life expectancy.

To learn more, a team of researchers in Italy looked at the medical files of 126 people with Cushing’s who were treated at a single hospital from 2001 to 2021 — a span of roughly 20 years. The patients’ median age at diagnosis was 39, and there were about three times as many women as men.

Producing too much cortisol is usually the result of an adenoma, or a noncancerous tumor, in the brain’s pituitary gland. This triggers the production of too much adrenocorticotropic hormone, which makes the adrenal glands produce excess cortisol.

When the pituitary tumor is small, it’s called a microadenoma; when it grows large, it’s called a macroadenoma. Of the 113 patients with available data on an adenoma, 91 (80.5%) had a microadenoma and 22 (19.5%) had a macroadenoma.

At the time of diagnosis, the most common clinical features were hypertension, commonly called high blood pressure, followed by excess weight, and abnormal blood fat levels known as dyslipidemia. More than half had glucose metabolism impairment, or abnormal blood sugar levels.

Most patients (89.7%) underwent a surgery called transsphenoidal adenomectomy to remove the pituitary tumor. One patient underwent a craniotomy, another type of surgery in which a pituitary tumor is removed.

Radiation therapy, or radiotherapy, was used to eliminate tumor cells in 34 patients (27%). Bilateral adrenalectomy, a surgery to remove both of the adrenal glands, was performed in 13 patients (10.3%), whereas in four individuals (3.2%), only one of the adrenal glands was removed.

Mortality rate higher among patients not in disease remission

Among all the patients, 78 — 62% — were in remission at their last examination, regardless of the treatment strategies used. All but one of the 48 patients (38.1%) with high cortisol levels at their last examination were on cortisol-lowering medications.

Over a median 130.5 months, or almost 11 years, there were 11 deaths. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular events, meaning those involving the heart and blood vessels, in four patients; infections and cancer were each the cause of death for two patients.

Patients who were older than 45 at diagnosis were 9.41 times more likely to die than those who were younger. They also were more likely to experience a cardiovascular event or thromboembolism, where a thrombus, or blood clot, blocks a blood vessel.

The presence of a macroadenoma on a first imaging scan also was linked to increased risk of death, while smoking increased the risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event.

Having persistent Cushing’s or at least three coexisting conditions at the last follow-up was linked to higher risk of death or cardiovascular events. However, “the timing of remission did not influence the mortality or the risk of complications,” the researchers wrote.

A standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was used to compare the observed death rate with the expected death rate in the general population. If the SMR is higher than one, then there is a higher number of deaths than it would be expected.

The SMR was 3.22, which means the group of patients “presented an increased mortality.” However, it was significantly higher among patients with persistent disease than among those in remission (4.99 vs. 1.66).

Disease remission seems to restore a normal life expectancy regardless of the timing and type of treatment used to achieve it. Thus, our aim as physicians is to pursue this goal by any means.

“Mortality was significantly higher in the patients with persistent disease,” the researchers wrote, “but it was similar to that of the general population in the patients in remission.”

“Disease remission seems to restore a normal life expectancy regardless of the timing and type of treatment used to achieve it. Thus, our aim as physicians is to pursue this goal by any means,” the researchers concluded.