Partial adrenal gland surgery may best treat Cushing’s syndrome

Shorter hospital stays, need for hydrocortisone therapy seen with approach

Surgery to remove adrenal tumors without taking the entire adrenal gland — given to Cushing’s syndrome patients to lower cortisol levels — associated with better outcomes than surgeries that remove all of the adrenal gland, a study reports.

Benefits included a shorter period of dependency on corticorteroids after surgery and a better control of cortisol levels.

The study, “Long-term outcome of retroperitoneoscopic partial versus total adrenalectomy in patients with Cushing’s syndrome,” was published in the World Journal of Surgery.

Adrenal gland tumor surgery is used to treat people with Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome comprises a group of conditions characterized by the excessive levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Often, Cushing’s is caused by a tumor in the pituitary gland, which produces greater amounts of the cortisol-controlling adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). In these cases, it is called Cushing’s disease.

In more rare cases, patients have tumors — benign (not cancerous) or malignant — in the adrenal glands that directly increase cortisol production. The adrenal glands sit atop the kidneys and play a crucial role in producing and releasing hormones, including cortisol, that regulate various body functions.

Surgery to remove the adrenal glands, a procedure called adrenalectomy, is a common treatment approach. It encompasses two types: one is a partial adrenalectomy that removes only the affected tissue, leaving much of the adrenal gland unaffected; the other is complete surgical resection, called a total adrenalectomy, in which the entire gland is removed.

Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy (PRA) is a minimally invasive way of performing an adrenalectomy. This technique involves accessing the adrenal glands from the back of the body through small incisions in the retroperitoneal space (the area behind the abdominal cavity).

Among its advantages are a shorter operating time, lesser blood loss, and faster recovery.

Surgeons with Helios University Hospital Wuppertal, in Germany, analyzed PRA outcomes in patients with Cushing’s syndrome.

Their goal was to examine how often the tumors come back after a partial adrenalectomy, and how this type of surgery affects the duration of corticosteroid therapy given after surgery.

The analysis covered 141 patients (129 women, 12 men; mean age of 45.7) who underwent PRA surgery between January 2000 and June 2020.

All had a benign tumor in the adrenal glands; among them, 105 patients had a partial and 36 a total adrenalectomy.

More total adrenalectomy patients stayed on cortisone therapy for over 2 years

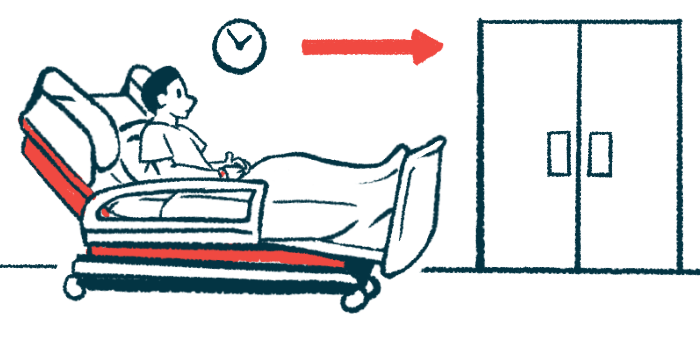

No surgery-related complications were reported, except for one case of bleeding following total adrenalectomy, which was successfully managed with medication. Patients were hospitalized for a mean length of 3.2 days (partial adrenalectomy) and 3.7 days (total adrenalectomy).

Hydrocortisone replacement therapy began on the day after the surgery, and continued after patients left the hospital. Those with manifest Cushing’s syndrome received oral corticoids (hydrocortisone) on the evening after surgery. Patients with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome — showing subtle abnormal cortisol levels but not obvious disease symptoms — were given oral corticoids if signs of hypocortisolism (low blood pressure, low blood sugar, fatigue, signs of confusion, fever, nausea) occurred.

Follow-up data were available for 83 patients (59%), 24 who had a partial adrenalectomy and 59 with a total adrenalectomy.

Patients were followed for a mean of about 8.9 years. Treatment with hydrocortisone after the surgery was kept for a mean of 21 months, and was longer in patients with a total adrenalectomy than a partial surgery (a median of 11 months vs. 9.5 months). This difference was not statistically significant, the scientists noted.

Significantly more patients in the total adrenalectomy group (15 or 25%) required corticosteroid therapy for more than two years than did those in the partial group (one or 4%).

A total of 16 patients (19%) discharged with corticosteroid therapy — 13 in the total adrenalectomy group — reported adverse effects. Twenty-one patients (25%) developed signs of adrenal insufficiency during follow up. Of note, adrenal insufficiency occurs when the adrenal glands are unable to produce sufficient amounts of hormones, including cortisol.

Cushing’s reappeared in one patient who underwent partial adrenalectomy, due to a second tumor being overlooked. This individual later underwent a total adrenalectomy.

The disease also reappeared in two patients who had a total adrenalectomy. One developed a tumor associated with subclinical Cushing’s and received treatment to control tumor growth, the other developed an abnormal mass and was under observation at the final study follow-up.

Overall, “partial adrenalectomy is associated with shorter duration of postoperative corticosteroids substitution period and significant lower risk of prolonged [low cortisol levels],” the researchers concluding, adding that study results “suggest that partial adrenalectomy can represent a safe operation for patients with unilateral Cushing’s syndrome.”