Case Reports Link Ectopic Cushing’s Syndrome to Small-Cell Lung Cancer Tumor

Tumors located outside of the pituitary gland — most commonly small-cell lung cancer — can lead to ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, a new case report shows.

The study with that finding, “Case-series of paraneoplastic Cushing syndrome in small-cell lung cancer,” was published in the journal Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism Case Reports.

Cushing syndrome develops when an individual is chronically exposed to high levels of glucocorticoids, such as cortisol. The most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome is a pituitary adenoma — a tumor of the pituitary gland — that secretes high levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which increases cortisol levels.

In a minority of patients (about 10-15 percent) high levels of ACTH are secreted by an ectopic extrapituitary neuroendocrine tumor — a tumor that occurs outside the pituitary gland.

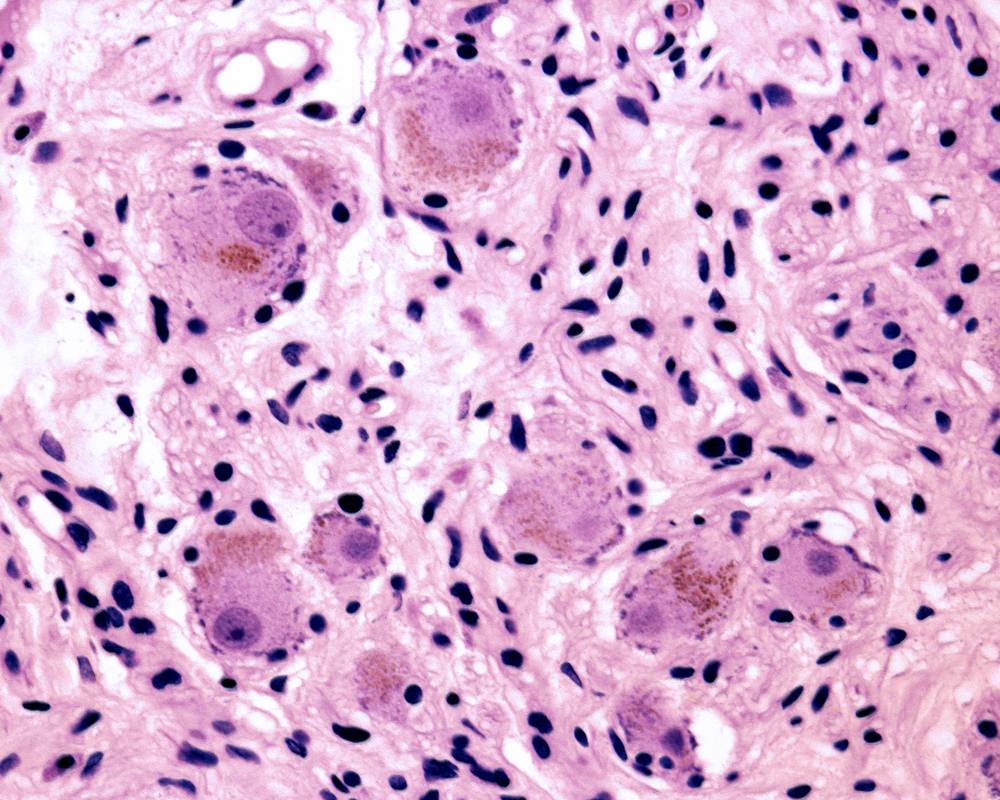

Most cases of extrapituatary tumors include small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and bronchial carcinoid tumors. However, making a diagnosis can be difficult because the symptoms usually are few and non-specific. Also, the tumor location often can be hard to determine, especially early in tumor development.

Therefore, to further study patients with ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, researchers described three cases of patients with extrapituitary tumors leading to Cushing’s syndrome.

The first case was that of a 46-year-old female with breast cancer who presented with hirsutism (excess hair), flushing, abdominal purple striae (stretch marks) and high blood pressure. Lung pathology showed the presence of small-cell lung cancer.

Laboratory tests revealed high ACTH levels. Due to an absence of pituitary issues, the patient was diagnosed with ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. For treatment of Cushing’s symptoms, the patient was given Aldactone (spironolactone) and Nizoral (ketoconazole). For cancer treatment, the patient underwent chemotherapy with doxorubicin and paclitaxel, and radiotherapy. Unfortunately, she died one year after diagnosis.

The second case was of a 51-year-old male whose symptoms included lethargy, fatigue, generalized edema (swelling), abdominal striae and buffalo hump. A chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a mass, which was found to be small-cell lung cancer. The patient also had high levels of cortisol, and ectopic Cushing’s syndrome was confirmed through additional testing. The patient was administered ketoconazole for hypercortisolism, and then chemotherapy for cancer. The patient passed away several months after diagnosis.

The third case was a 41-year-old male who presented with weight loss, right upper-quadrant tenderness, bilateral pitting edema on lower limbs, and high blood pressure. Further testing revealed cancer of unknown origin, which was mainly present in the liver, but also in other organs. Physicians detected high cortisol levels, and performed further analysis to confirm ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. The patient was treated with carboplatin and etoposide as chemotherapy. He did not receive any treatment for Cushing’s and passed away one year after diagnosis.

These three case studies suggest that ectopic Cushing’s syndrome can occur from different types of cancers, with the majority originating in the lung — particularly small-cell lung cancer. Diagnosis for these patients was carried out by determining cortisol levels, ACTH and dexamethasone suppression test. Treatment options for these patients included surgery, chemotherapy and targeted treatment.

The invesigators concluded that ectopic Cushing’s syndrome “should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any patient presenting with the phenotype of [Cushing’s syndrome], hypertension, hyperglycemia, electrolytes disturbance, with or without underlying cancer.”