More biomarkers needed to support Cushing’s syndrome diagnosis

Observational study says these would allow better assessment of children

More biomarkers are necessary for the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome subtypes in children and adolescents, as well as to predict disease progression more effectively — allowing for quicker and less invasive assessments of patients.

That’s according to the results of a new, large, observational study, which also reported on data on the prevalence of Cushing’s-related health complications in pediatric patients, together with their long-term outcomes.

“This extensive description of a unique cohort [group] of paediatric patients with Cushing syndrome has the potential to inform diagnostic workup, preventative actions, and follow-up of children with this rare [disease],” the researchers wrote.

These findings should help clinicians in making a better differential diagnosis — one in which a patient’s symptoms match more than one condition and additional tests are needed to correctly identify the specific disease — of Cushing’s syndrome.

The study, “Paediatric Cushing syndrome: a prospective, multisite, observational cohort study,” was published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

Study analyzed data from 342 pediatric Cushing’s syndrome patients

While Cushing’s syndrome — a condition triggered by high cortisol levels, or hypercortisolism — typically occurs in adults between the ages of 20 and 50, rare cases have been described in children and adolescents. These cases correspond to about 5%-7% of all people with the condition.

As in adults, the disease in pediatric patients is usually caused by a tumor in the brain’s pituitary gland that leads to the excessive production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which prompts the adrenal glands that sit atop the kidneys to produce excessive cortisol. Named Cushing’s disease, it’s a specific type of Cushing’s syndrome.

The disease also can be caused by ACTH-producing tumors occurring outside the pituitary gland — in which case it’s called ectopic Cushing’s — or by tumors in the adrenal glands independent of ACTH production.

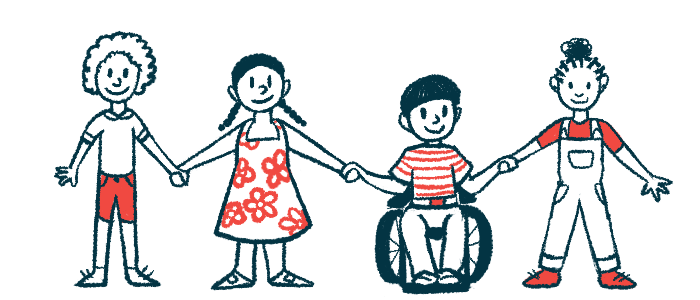

Importantly, the disease symptoms in children differ from those in adults and can lead to growth issues, such as weight gain with height deceleration, and delayed or suppressed puberty. Children with the condition also may experience mental health and cognitive problems.

All this makes a Cushing’s diagnosis challenging, commonly leading to delayed evaluation and oftentimes lags in treatment.

To know more, researchers in the U.S. conducted an observational study to describe the physical, clinical, and biochemical — an analysis of substances in the body — characteristics of children and adolescents with Cushing’s syndrome. They also sought data on disease-related outcomes that may help diagnose, treat, and manage the condition.

To that end, they analyzed available information from 342 children and adolescents, ages 18 and younger, who were diagnosed with Cushing’s. Most — 278 patients — were referred from centers in the U.S., while 64 were from centers outside the U.S.

Overall, more than half of the patients (56%) were female. However, when considering only those diagnosed before puberty, 61% were male. Among those diagnosed after puberty, nearly two-thirds (64%) were female.

Moreover, most had Cushing’s disease (76%), while 22% had Cushing’s caused by adrenal tumors, and 2% had ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Those with adrenal Cushing’s were the youngest at diagnosis, followed by patients with Cushing’s disease and the ones with ectopic disease (median 10.4 vs. 13 vs. 13.4 years).

Patients were diagnosed at a median time of two years after the first symptoms. The time between the disease’s first signs until diagnosis was shorter for individuals with adrenal-associated Cushing’s syndrome than for those with Cushing’s disease (median duration 1.5 vs. 2.5 years).

Multiple tests used to help clinicians diagnose three Cushing’s subtypes

The most prevalent symptoms were fatigue and loss of energy, headaches, acne, and mood or behavioral changes, including anxiety and depressive mood. Most patients also had stretch marks that were thin and with a light appearance.

At diagnosis, there were no differences in the patients’ body characteristics regarding height, weight, and body mass index adjusted for the child’s age and sex.

Regarding the results of biochemical analysis, blood cortisol levels were similar among the three Cushing’s subtypes. However, urine cortisol levels were higher in patients with ectopic syndrome, followed by Cushing’s disease and adrenal-associated Cushing’s (15.5 vs. 3.9 vs 1.5 times higher than the upper reference values).

Similarly, ACTH levels were significantly higher in patients with ectopic Cushing’s compared with those with Cushing’s (66.8 vs. 42.3 picograms/mL). For the ones with adrenal-related Cushing’s, ACTH levels were below the lower reference value.

Positive responses in noninvasive tests — an increase in cortisol levels in the corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test or desmopressin test, and a reduction in cortisol with the high-dose dexamethasone — were consistent with a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease.

Moreover, an invasive procedure that measures ACTH levels in the veins that drain the pituitary gland, known as a inferior petrosal sinus sampling procedure, was effective at diagnosing Cushing’s disease. This was as expected, considering that it’s the gold standard test for the condition.

More biomarkers for disease-specific diagnosis and prognosis are essential for less invasive and more time-sensitive evaluation of patients with Cushing syndrome.

Data on surgery for Cushing’s disease was available for 251 participants, with 223 achieving disease remission after a minimally invasive procedure to remove the pituitary tumor, and 28 patients having persistent disease. The disease recurred in 16% of the patients who had an initial remission, at a median time of 30 months or 2.5 years after the procedure.

Among all patients, the most common Cushing’s-related health complications were high blood pressure (in 52%), high blood sugar levels (in 30%), elevated liver enzymes (in 64%), and abnormal values of fats in the blood (in 48%).

Overall, the study provides “information and guidance on the diagnostic workup, as well as for screening for related complications.”

“Prognosis of Cushing[’s] syndrome remains excellent if diagnosis and management [are] performed by specialists with experience of this disorder,” the researchers concluded.

“However, more biomarkers for disease-specific diagnosis and prognosis are essential for less invasive and more time-sensitive evaluation of patients with Cushing syndrome,” the team noted.